Hugh Ferriss

- BORN

-

July 12, 1889

Saint Louis, Missouri

- DIED

-

January 29, 1962

New York, New York

- EDUCATION

-

Washington University in St. Louis

Saint Louis, MissouriManual Training School (St. Louis)

Saint Louis, Missouri

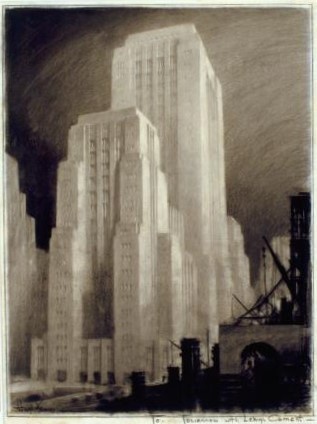

During his lifetime, Hugh Ferriss was called “the Nation’s number one Architectural artist.” Ferriss’s masterful depictions of American architecture, with dramatic structures silhouetted against misty backdrops, chronicled the development of industry, urbanism, and planning in pre-World War II United States. While Ferriss’s visions were vast and monumental, his drawings all reflect a simple premise: that “the underlying truth of a building is that it is a mass in space” ("Visions in Charcoal," 54).

Ferriss was born in St. Louis in 1889. His father, Franklin Ferriss, sat on the Missouri Supreme Court and taught at Washington University in the School of Law. Ferriss attended the Manual Training School in St. Louis, and then studied at Washington University, graduating with a degree in architecture in 1911. As a student, he was highly active, serving as class president and student body president, as well as being involved in several fraternities.

In 1912, Ferriss moved to New York City, where he entered the practice of Cass Gilbert, a renowned architect who had previously designed buildings for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, as well as the St. Louis Central Library, which was under construction that year. Ferriss’ first assignment in the office was to join a team working on drawings for the Woolworth Building. This served as an initial introduction to the skyscraper, a subject that would continue to fascinate Ferriss throughout his career.

By 1915, Ferriss departed Gilbert’s studio and set up his independent practice, focusing largely on architectural representation and rendering. Ferriss’s architectural renderings are distinctive and captivating. Using graphite and charcoal to evoke a dark and moody atmosphere, the artist reduced building form to its essential mass, and employed dramatic lighting to make the architecture appear to emerge from the brumous backdrop.

In 1922, Ferriss produced a series of set-back studies, demonstrating the effects of New York’s 1916 zoning laws on building form. In the series, various set-backs are carved out of an initial ‘envelope,’ resulting in a tiered expression that can still be seen in many tall building designs to this day. This series was notable for the fact that it actually manipulated building form through drawing, rather than merely representing a finalized design. This series of set-back studies appeared in Ferriss’s 1929 landmark work, The Metropolis of Tomorrow, a culmination of Ferriss’ observations on architecture and urbanism. The book outlines Ferriss’s vision for the future of American city planning and construction in three parts: “Cities of Today,” “Projected Trends,” and “An Imaginary Metropolis.” Interspersed with Ferriss’s drawings, the text considers the various building forms and types that make up the contemporary urban fabric, and speculates on how these forms will be adapted in the future. Here, Ferriss’s distinctive style can be seen at its full effect: buildings are stripped of detail and ornament, and instead speak to a more symbolic vision for the future of American cities. These images have frequently been compared to the Prisons of Giambattista Piranesi, an 18th-century Italian etcher who similarly projected urban conditions into disorienting imaginary architectures.

Ferriss’s visionary work in architectural rendering made him one of the most well-known architects of his day, though he rarely engaged in design-for-construction. He became one of the most sought-after renderers among the architectural community in New York, and taught classes in architectural drawing and rendering across the United States. He served as a consultant to the architectural committees for the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago (1933) and New York World’s Fair (1939), and later was involved in the design for the United Nations Headquarters in the late 1940s.

Ferriss died in 1962 in New York City and is interred at Bellefontaine Cemetery in Saint Louis, Missouri.

Hugh Ferriss Solo Exhibition

Organized by Paint Box Gallery

Organized by Paint Box Gallery

Architectural League of New York Exhibition

Organized by Architectural League of New York

Organized by Architectural League of New York

Hugh Ferriss Solo Exhibition

Organized by Washington University

Organized by Washington University

Awards & Exhibitions 5

Hugh Ferriss Solo Exhibition

Organized by Paint Box Gallery

Organized by Paint Box Gallery

Architectural League of New York Exhibition

Organized by Architectural League of New York

Organized by Architectural League of New York

Hugh Ferriss Solo Exhibition

Organized by Washington University

Organized by Washington University

References

Artist clippings file is available at:

“Hugh Ferriss: Artist File.” St. Louis Public Library, St. Louis, Missouri.

Bibliography

Select Sources

Carol Willis, "Ferriss, Hugh," Grove Art Online (2003), accessed March 12, 2022, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000028059.

Ferriss, Hugh. _The Metropolis of Tomorrow. _(Mineola, N.Y. : Dover Publications, 2005).

"Visions in Charcoal," Preservation, January/February 2001, 53.

Ferriss, Hugh. "A New Type of Building," The Christian Science Monitor, August 27, 1923.

Core Reference Sources

askART (database), askART, https://www.askart.com/.

Union List of Artist Names Online, Getty Research Institute, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/ulan/.

Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/.

E. Bénézit, Dictionary of Artists (Paris: Gründ, 2006).

Peter H. Falk, et. al, Who was Who in American Art, 1564-1975: 400 Years of Artists in America (Madison: Sound View Press, 1999).

St. Louis Public Library, St. Louis Art History Project: Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Artists (St. Louis: St. Louis Public Library, 1989).

Mantle Fielding, Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors & Engravers (Poughkeepsie: Apollo, 1983).

Image Credits

Artwork

Hugh Ferriss, New York Public Library, circa 1918.

Black crayon on paper on board, architectural drawing, 17 5/8 x 23 1/2 in.

Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, NYDA.1000.001.00081.

Hugh Ferriss, Imaginary drawings: Skyscraper, 1925.

Charcoal/Paper, architectural drawing, 25 3/4 x 19 3/8 in.

Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, NYDA.1000.001.00294.

Contributors

John Knuteson, St. Louis Public Library

Artist Record Published

Published on May 7, 2022

Learn more

References

Artist clippings file is available at:

“Hugh Ferriss: Artist File.” St. Louis Public Library, St. Louis, Missouri.

Bibliography

Select Sources

Carol Willis, "Ferriss, Hugh," Grove Art Online (2003), accessed March 12, 2022, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000028059.

Ferriss, Hugh. _The Metropolis of Tomorrow. _(Mineola, N.Y. : Dover Publications, 2005).

"Visions in Charcoal," Preservation, January/February 2001, 53.

Ferriss, Hugh. "A New Type of Building," The Christian Science Monitor, August 27, 1923.

Core Reference Sources

askART (database), askART, https://www.askart.com/.

Union List of Artist Names Online, Getty Research Institute, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/ulan/.

Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/.

E. Bénézit, Dictionary of Artists (Paris: Gründ, 2006).

Peter H. Falk, et. al, Who was Who in American Art, 1564-1975: 400 Years of Artists in America (Madison: Sound View Press, 1999).

St. Louis Public Library, St. Louis Art History Project: Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Artists (St. Louis: St. Louis Public Library, 1989).

Mantle Fielding, Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors & Engravers (Poughkeepsie: Apollo, 1983).

Contributors

John Knuteson, St. Louis Public Library

Artist Record Published

Published on May 7, 2022

Updated on None