Jesse Howard

- BORN

-

June 4, 1885

Shamrock, Missouri

- DIED

-

November 21, 1983

Fulton, Missouri

Jesse Clyde Howard was a folk artist and farmer who created thousands of provocative signs declaring his beliefs about religion, morality and politics during the later decades of his life. While Howard’s work wasn’t appreciated within his own community of Fulton, Missouri, during his life, his signs and sculptures fascinated an international audience who viewed them as groundbreaking works of contemporary art.

Jesse Howard was born the youngest of ten siblings in 1885 on a small farm in rural Missouri. With only a sixth-grade education at age eighteen, Howard left home and spent two years traveling the United States, working temporary jobs on farms and railroads. After returning home, he married Maude Linton in 1916 and continued working as a farmer while raising their children. After World War II, he and his family purchased a property in Fulton named "Sorehead Hill." Howard then began helping a man named Ed M. Peacock put on weekend shows of antique farming equipment that drew visitors from miles away. The experience profoundly affected Howard, inspiring him to transform Sorehead Hill into a tourist attraction.

Howard originally envisioned a space where visitors would come to view handcrafted curiosities and learn lessons from the Bible. Among his first creations were seven symbolic burial mounds for religious figures, a version of Jacob's Well, and a replica of Haman's gallows from the Old Testament. Yet Howard's ambitions were soured by hostility from his neighbors. Howard created his first sign after one of his hand-carved model airplanes was destroyed. As theft and vandalism of his work continued, Howard created more and more signs, covering his property with expressions of outrage and indignation. As time went on, his signs became more contemplative, frequently quoting newspapers, the Bible, a farmer's almanac, and a dictionary in an attempt to express his beliefs.

Jesse Howard was eighty-three years old when his first artistic recognition came in the form of an article titled "The Grass-Roots Artist," published by Gregg Blasdel in Art In America. After Blasdel's article, Howard began receiving waves of visitors and exhibition offers. Dale Eldred, William Volkersz, and other professors from the Kansas City Art Institute regularly visited Howard and held exhibitions of his work. Other young artists like Roger Brown saw Howard as a visionary. By the time of his death in 1983, his signs and sculptures were preserved in the collections of many major art museums, and since then his work has been exhibited widely.

Note

Jesse Clyde Howard's middle name is listed alternatively as Ernest.

Naives and Visionaries Exhibition

Organized by Walker Art Center

Organized by Walker Art Center

The Work of Jesse Howard Exhibition

Organized by Charlotte Crosby Kemper Gallery

Organized by Charlotte Crosby Kemper Gallery

Tulsa First National Bank Mural Competition

Organized by Philadelphia College of Art

Organized by Philadelphia College of Art

Missouri Artist Jesse Howard Exhibition

Organized by University of Missouri Gallery of Art

Organized by University of Missouri Gallery of Art

World of James Yeatman Exhibition

Organized by Mid-America Arts Alliance

Organized by Mid-America Arts Alliance

Jesse Howard & Roger Brown: Now Read On Exhibition

Organized by Kansas City Art Institute

Organized by Kansas City Art Institute

Jesse Howard: Thy Kingdom Come Exhibition

Organized by Contemporary Art Museum

Organized by Contemporary Art Museum

Awards & Exhibitions 16

Naives and Visionaries Exhibition

Organized by Walker Art Center

Organized by Walker Art Center

The Work of Jesse Howard Exhibition

Organized by Charlotte Crosby Kemper Gallery

Organized by Charlotte Crosby Kemper Gallery

Tulsa First National Bank Mural Competition

Organized by Philadelphia College of Art

Organized by Philadelphia College of Art

Missouri Artist Jesse Howard Exhibition

Organized by University of Missouri Gallery of Art

Organized by University of Missouri Gallery of Art

World of James Yeatman Exhibition

Organized by Mid-America Arts Alliance

Organized by Mid-America Arts Alliance

Jesse Howard & Roger Brown: Now Read On Exhibition

Organized by Kansas City Art Institute

Organized by Kansas City Art Institute

Jesse Howard: Thy Kingdom Come Exhibition

Organized by Contemporary Art Museum

Organized by Contemporary Art Museum

References

Artist clippings file is available at:

Jannes Library, Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, Missouri

Bibliography

Select Sources

"Jesse Ernest (twin to Myrtle) Howard, 1885-1983," Ancestry, accessed May 1, 2021.

Donald Hoffman, "Jesse Howard: His Art Is From the Heart," Kansas City Star, April 3, 1977.

"Jesse Howard: Thy Kingdom Come," Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, accessed April 23, 2021 https://camstl.org/exhibitions/jesse-howard-thy-kingdom-come/.

Ann Kleener, "Jesse Howard: A Personal Impression of an American Artist," in Missouri Artist Jesse Howard, With A Contemplation On Idiosyncratic Art, ed. Howard W. Marshall (Columbia: University of Missouri-Columbia, 1983), 12-24.

Gregg Blasdel, "The Grass-Roots Artist," Art In America 56, no. 5 (September 1968): 20-41.

Lisa Stone, "Free Speech from the Home Front," in Roger Brown & Jesse Howard: Now Read On, ed. Margaret Brommelsiek (Kansas City: UMKC Center for Creative Studies, 2005), 9-14.

"Jesse Howard: Biography" in Roger Brown & Jesse Howard: Now Read On, ed. Margaret Brommelsiek (Kansas City: UMKC Center for Creative Studies, 2005), 75-78.

"Jesse Howard: Bibliography, Exhibitions & Collections," in Roger Brown & Jesse Howard: Now Read On, ed. Margaret Brommelsiek (Kansas City: UMKC Center for Creative Studies, 2005), 79-86.

Richard Rhodes, "Jesse Howard: Signs and Wonders," in Naives and Visionaries, ed. Martin Friedman (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1974), 61-69.

Edwin Smith, "Grass-root Sculptors In Missouri: A Photographic Essay" (Cape Girardeau: University Museum, Southeast Missouri State University, 1981), 25.

Core Reference Sources

askART (database), askART, https://www.askart.com/.

Image Credits

Artwork

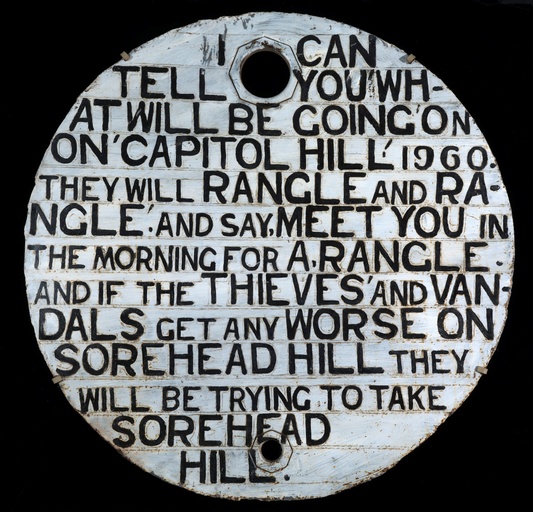

Jesse Howard, Untitled (#79), 1960.

Paint on metal, 22 1/4 in. diameter.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Kohler Foundation, Inc. in collaboration with the Kansas City Art Institute, 2017.12.2.

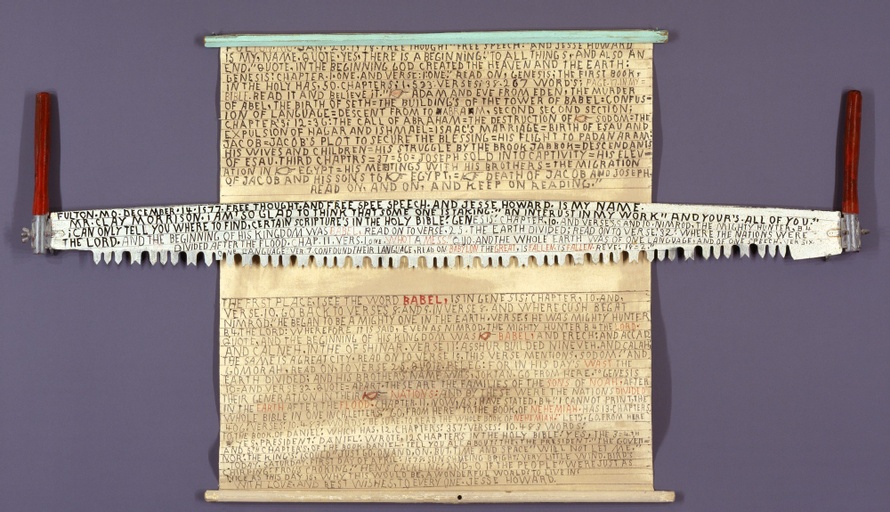

Jesse Howard, The Saw and the Scroll, 1977-1978.

Acrylic and crayon on canvas and wood; acrylic on metal and wood, 39 3/4 x 71 x 1 1/2 in.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Chuck and Jan Rosenak and museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, 1997.124.26A-B.

Portrait of Artist

L.B. Burrow, Jesse Howard, 1972.

Gelatin silver print, 9 7/8 x 8 in.

John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection, gift of Kohler Foundation Inc., in partnership with the Kansas City Art Institute.

Contributors

Elinore Noyes, Kansas City Art Institute

Artist Record Published

Published on September 20, 2021

Learn more

References

Artist clippings file is available at:

Jannes Library, Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, Missouri

Artist’s work in these institutions’ collections

Kansas City Art Institute

Bibliography

Select Sources

"Jesse Ernest (twin to Myrtle) Howard, 1885-1983," Ancestry, accessed May 1, 2021.

Donald Hoffman, "Jesse Howard: His Art Is From the Heart," Kansas City Star, April 3, 1977.

"Jesse Howard: Thy Kingdom Come," Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, accessed April 23, 2021 https://camstl.org/exhibitions/jesse-howard-thy-kingdom-come/.

Ann Kleener, "Jesse Howard: A Personal Impression of an American Artist," in Missouri Artist Jesse Howard, With A Contemplation On Idiosyncratic Art, ed. Howard W. Marshall (Columbia: University of Missouri-Columbia, 1983), 12-24.

Gregg Blasdel, "The Grass-Roots Artist," Art In America 56, no. 5 (September 1968): 20-41.

Lisa Stone, "Free Speech from the Home Front," in Roger Brown & Jesse Howard: Now Read On, ed. Margaret Brommelsiek (Kansas City: UMKC Center for Creative Studies, 2005), 9-14.

"Jesse Howard: Biography" in Roger Brown & Jesse Howard: Now Read On, ed. Margaret Brommelsiek (Kansas City: UMKC Center for Creative Studies, 2005), 75-78.

"Jesse Howard: Bibliography, Exhibitions & Collections," in Roger Brown & Jesse Howard: Now Read On, ed. Margaret Brommelsiek (Kansas City: UMKC Center for Creative Studies, 2005), 79-86.

Richard Rhodes, "Jesse Howard: Signs and Wonders," in Naives and Visionaries, ed. Martin Friedman (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 1974), 61-69.

Edwin Smith, "Grass-root Sculptors In Missouri: A Photographic Essay" (Cape Girardeau: University Museum, Southeast Missouri State University, 1981), 25.

Core Reference Sources

askART (database), askART, https://www.askart.com/.

Contributors

Elinore Noyes, Kansas City Art Institute

Artist Record Published

Published on September 20, 2021

Updated on None